Slum2School's Efforts In Response To The Pandemic

Transitioning After the Lockdown: What is the Practical Way Forward for Nigeria?

Strengthened Health Capacity in all Tiers of Health Facilities in the Country

Primary, secondary, and tertiary health facility staff in all states in the country should have strengthened surveillance capacity. This entails rapidly detecting and isolating suspect cases. It should be enforced from health posts and primary health centres (PHCs) to tertiary facilities. While it may be unrealistic to expect PHCs to test, appropriate guidance on detecting and isolation should be given. Infection Prevention and Control (IPC) measures should be in place in all health institutions, public and private. Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) should be available to all categories of health facilities. It is important health providers in the traditional sector are engaged and made aware of IPC measures and how to escalate suspected cases. Strengthening PHCs and traditional healers are critical because they are the first port of call for the majority of health seekers.

Intensified Community Engagement and Risk Communication

Risk communication without adequate community engagement essentially takes a top-down approach. Public health responses by the government without community members showing ownership might undermine efforts to limit transmission. The Ebola outbreak, in parts of West Africa, affirmed the value of effective community engagement. Whilst risk communication is in place, a smooth transition from the lockdown to normalcy with little or no widespread transmission will depend on how communities are supported to consider themselves as partners in the response. Engaging religious leaders is vital in meeting this recommendation.

Nigerians need to understand that behavioural preventive measures must be maintained, even after the lockdown, and that all individuals have key roles in limiting transmission. Recently, I came across a cartoon public health communication, depicting how the virus spreads from person to person, I honestly felt it was the most impactful educational material I had seen.

Strengthened Capacity to Mass Test for SARS- CoV-2

As a country, we need to prepare and prioritize mass testing in Lagos, Abuja and now alarming Kano. There are useful lessons we could learn from South Korea, a country with a similar population density as Nigeria. Mass testing and technology have been proven to be effective in South Korea’s flattening of the epidemic curve. Since the pandemic is relatively low in Nigeria, mass testing will be critical in transitioning to normalcy. I believe technology can play a key role in rapid detection and contact tracing. Singapore, scaled-up contact tracing using technology. Telkom, the largest telecom firm in South Africa collaborated with Samsung to use mobile devices to support contact tracing efforts of the government. IT experts should be engaged to explore the feasibility of such intervention in the Nigerian context. It is encouraging that molecular testing laboratories across the country have increased to 15 and the Nigeria Centre for Disease Control (NCDC) is working tirelessly to scale-up testing capacity. NCDC case summary reports that approximately 10918 samples have been tested with 1273 laboratory-confirmed cases as of 26th April 2020. This is a far cry from samples tested by our neighbours, Ghana.

Protect the High-risk Population and High Vulnerability Settings.

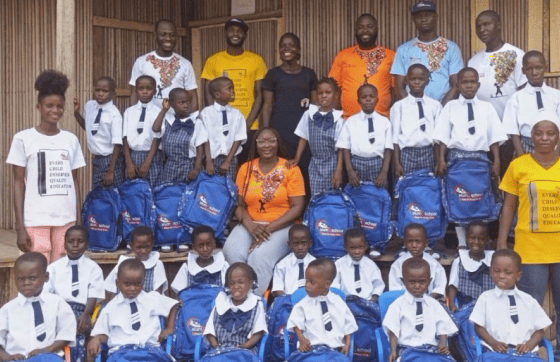

Studies have shown the predictors of fatality and critical cases in COVID-19 to be advanced age, presence of comorbidities, and the presence of secondary infection. Analyses showed that individuals with cardiovascular diseases have an increased risk of death and mortality increases as from the age of 60 and worsens with increasing age. This implies that post lockdown, special care should be given to this category of people. High vulnerability settings like IDP camps, prisons, and slums need to be protected. Slums house the poorest in the society, the COVID-19 epicentre in Nigeria, Lagos, currently has about 66% of its residents in slums in and around the lagoons. IDP camps, prisons, and slums in Nigeria have a peculiar challenge, overcrowding, therefore preventive measures like physical distancing and self-isolation are daunting measures. It is impressive that the federal and various state governments have approved the release of some prisoners to decongest the facilities.

Resumption of Social Activities and Educational Activities

As recommended, returning to normalcy should be phased. In the resumption of social activities, preventive measures such as physical distancing, temperature checks, hand hygiene should be enforced and monitored in public places and social activities need to be prioritized. Anambra State, a state with no active case, recently resumed social activities amidst stringent preventive measures, it will be useful to study the trends following this resumption. A mathematical model of non-pharmaceutical intervention (case isolation, household quarantine, school closure, and workplace closure) strategies in the context of the influenza pandemic reported that school closure is the single most effective intervention among all NPIs. Considering this evidence, school closures should still be in place. It is impressive the federal government is making attempts to engage primary and secondary school students online.

Resumption of Economic Activities in the Informal and Formal Sectors

Appropriate community engagement will provide more clarity to workers in the informal sector on how to conduct business safely. As more workers in the formal sector that can work from home should be encouraged to do so. Senior cadre officers in government parastatals should return to work first before the other staff. Preventive measures must be in place in all work environments. Workers in both the formal and informal sectors should be monitored to strengthen preventive measures in their places of work. With the slow resumption of activities, there is a need to monitor the transport system and ensure stricter compliance with guidelines.